In his review of an exhibition of Sylvia Plimack Mangold’s at the Brooke Alexander Gallery in New York, Robert Kushner described the critical no-man’s-land that Plimack Mangold’s landscapes have long occupied. “Realists don’t know what to do with Mangold’s intellectual clarity and scrappy nonprettiness,” he wrote. “Hard-core abstractionists can’t embrace the subject matter. The gloom-and-doom contingent find the life-affirming qualities of her work a little uncomfortable. This leaves Mangold in an artistic arena of her own creation, where rules are defined and broken according to her uncompromising demands on herself and the profound integrity of her paintings.”

Sylvia Plimack Mangold was born in 1938 in the Bronx and studied at the Cooper Union School of Art in Manhattan before receiving her BFA from the Yale University School of Art in 1961. At Yale she met and married artist Robert Mangold, who would later become a pioneer of minimal painting. After their schooling, the couple moved to New York, where they managed an apartment building to make a living. Their friends included Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre, sculptors who were investigating primary forms and eliminating illusionist references to the real world, and sculptor Eva Hesse, a forerunner of a movement later called antiform. In this climate, Plimack Mangold began painting pictures of floors, searching, she has said, for “visual consistency” and “a structure of a system that defined space.” In order to keep focused on literal space, she sometimes included in her compositions the image of a ruler or of masking tape defining a rectangle. Illusion became a “by-product” of her investigation of three-dimensional space.

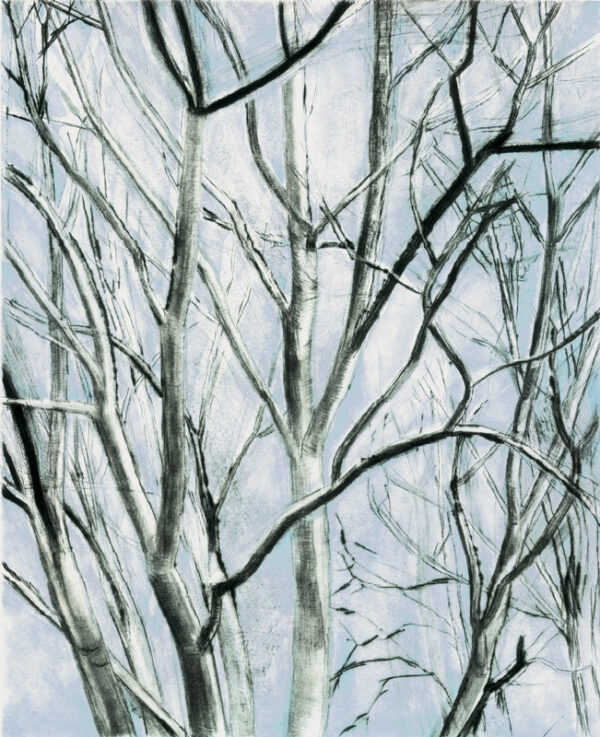

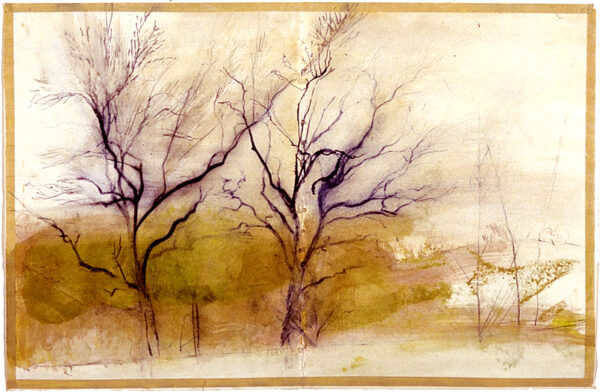

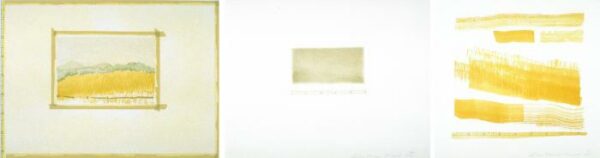

After leaving New York City in 1971, she and Robert Mangold moved first to the Catskill Mountains and then to the Hudson River Valley. It was there that Plimack Mangold began painting landscapes, allowing three-dimensional space to become the pure goal of her work. Though in method and spirit her art is traditional, heir to that of nineteenth-century painters, the fact that she came into her own at a time when abstract expressionism was occupying much of the attention of the international art world instilled her approach with a very modern intellectual rigor. It is this seeming paradox that makes her landscapes so powerful. “Plimack Mangold’s intention is not either/or,” Kathan Brown wrote in her 1999 book Why Draw a Landscape? “She can intend to investigate painting as a process, and she can also intend to observe the trees. In pursuing these two approaches simultaneously, she has hit on a way of painting that is distinctly hers.”

Sylvia Plimack Mangold is represented by Pace Gallery in New York and by Annemarie Verna Gallery in Zurich, Switzerland. Her work is the collections of more than fifteen American museums, including the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and the Yale University Art Gallery in New Haven, Connecticut.

-Rachel Lyon, Crown Point Press

WHY DRAW A LANDSCAPE?