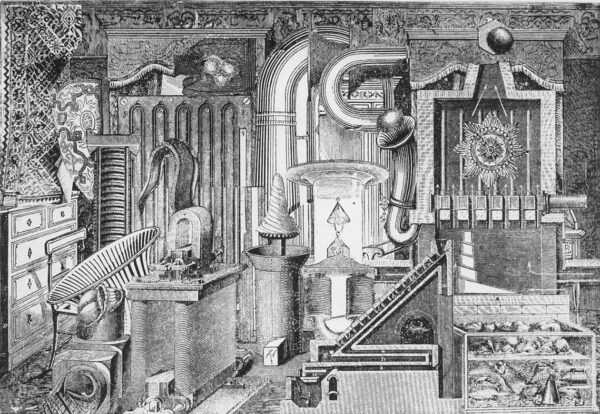

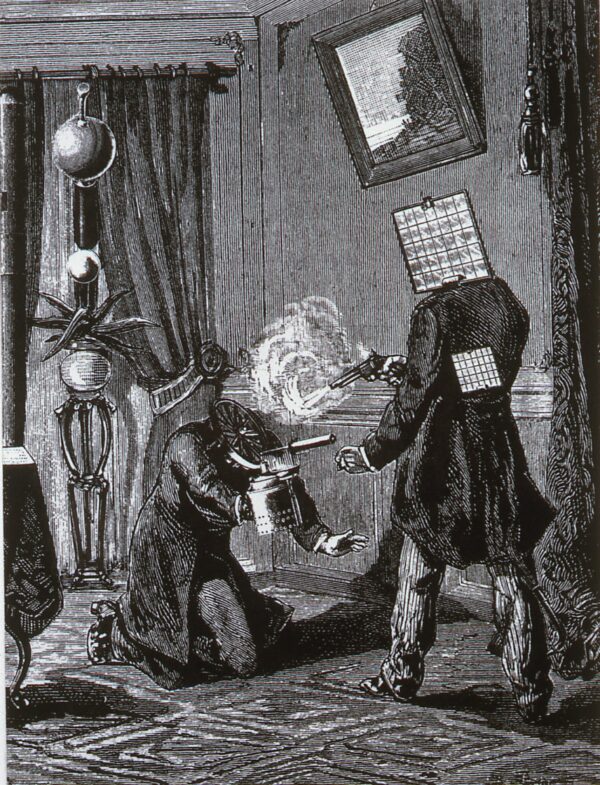

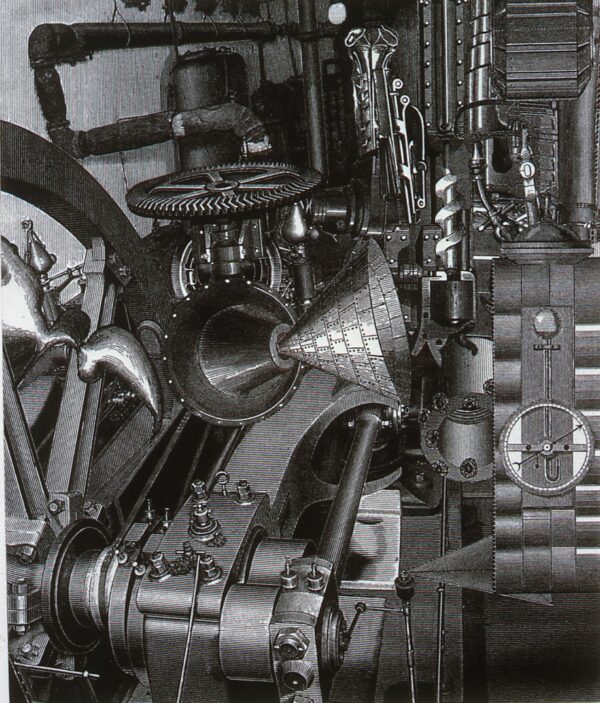

Photoetching.

13¼ x 9"; 18 x 15". 10.

Crown Point Press and Kathan Brown.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

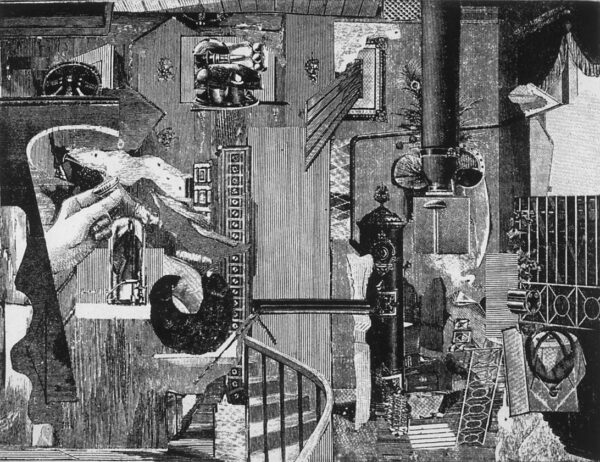

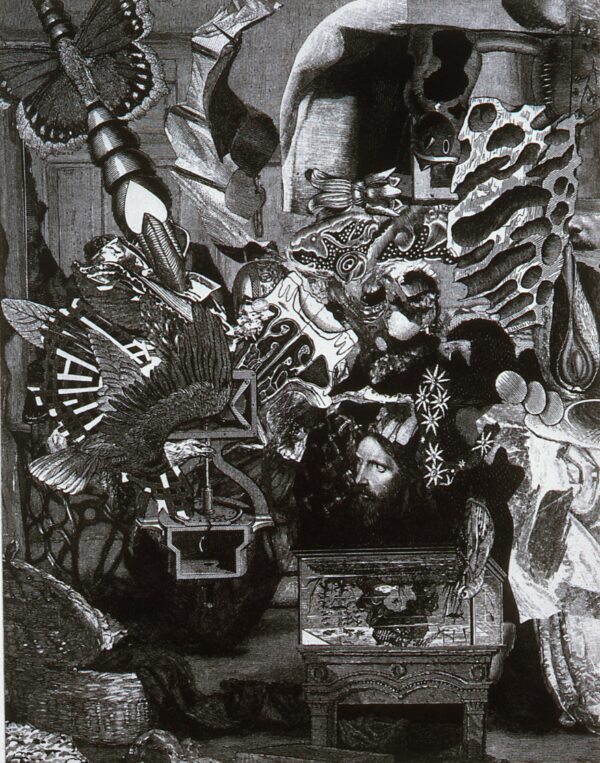

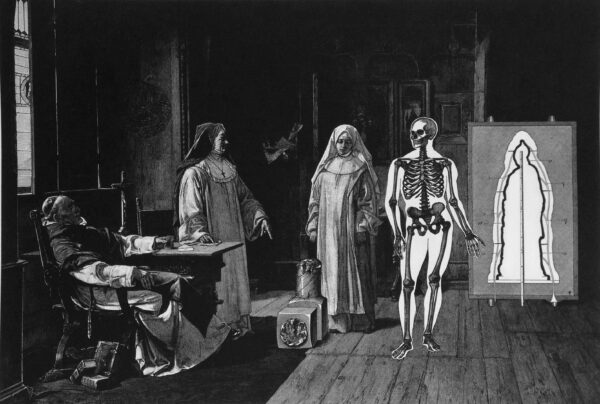

Photoetching.

7½ x 11"; 18 x 15". 10.

Crown Point Press and Kathan Brown.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

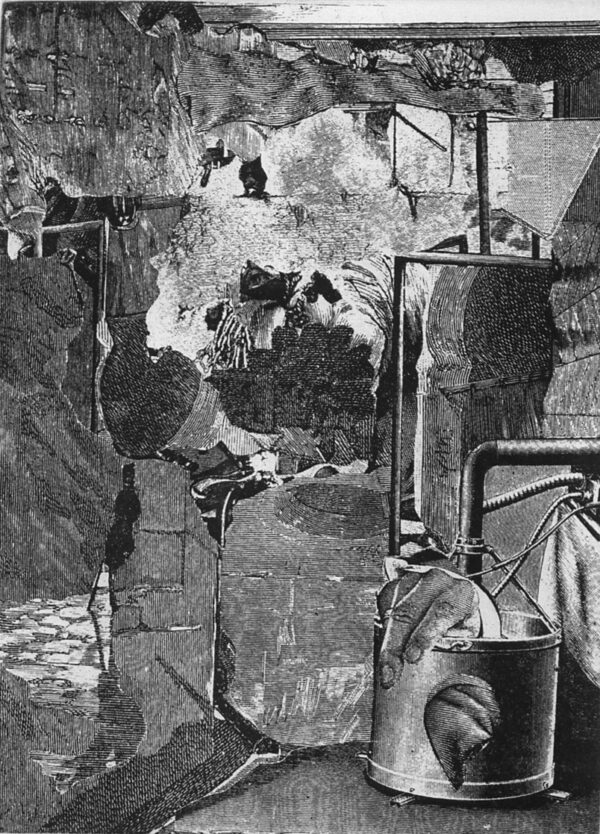

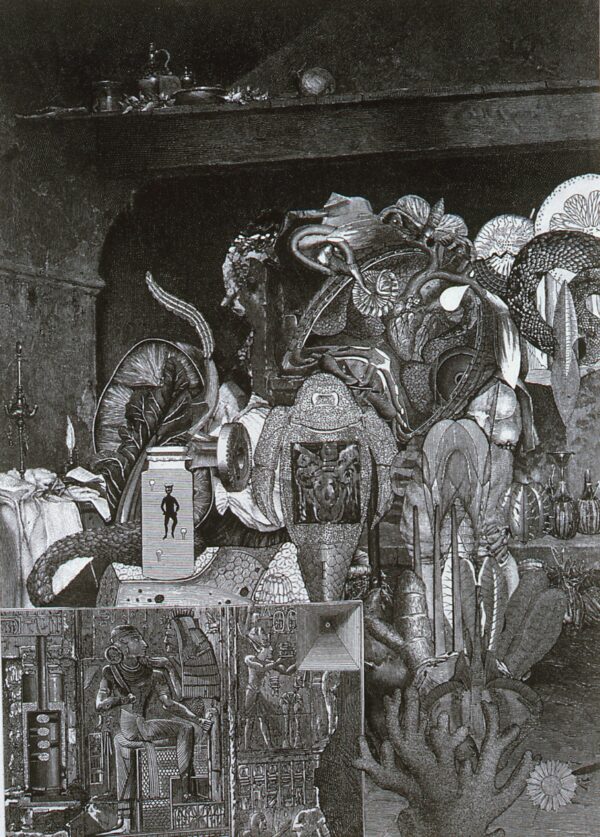

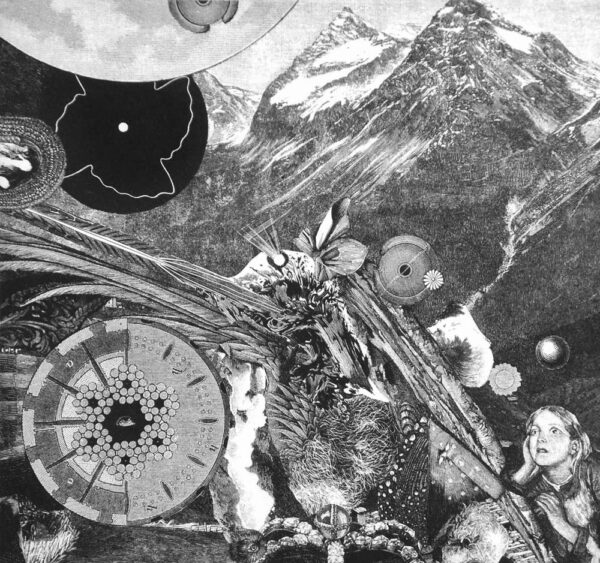

Photoetching.

7 x 9"; 18 x 15". 10.

Crown Point Press and Kathan Brown.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

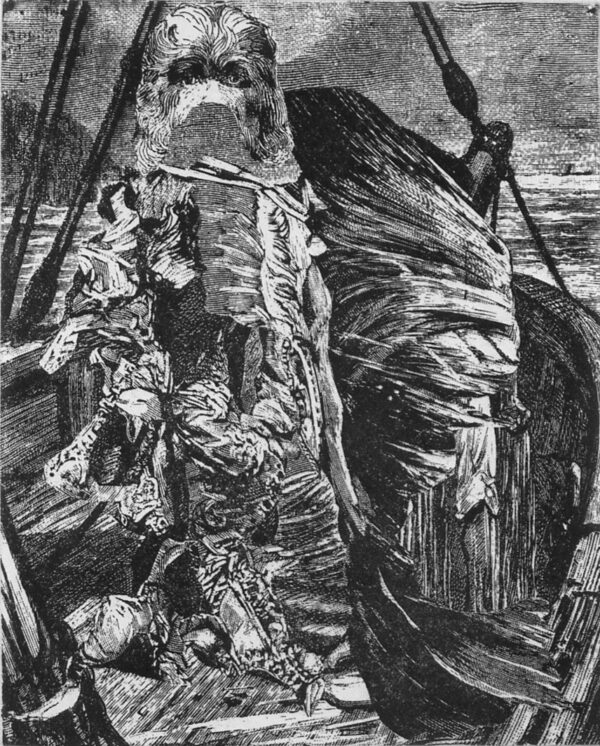

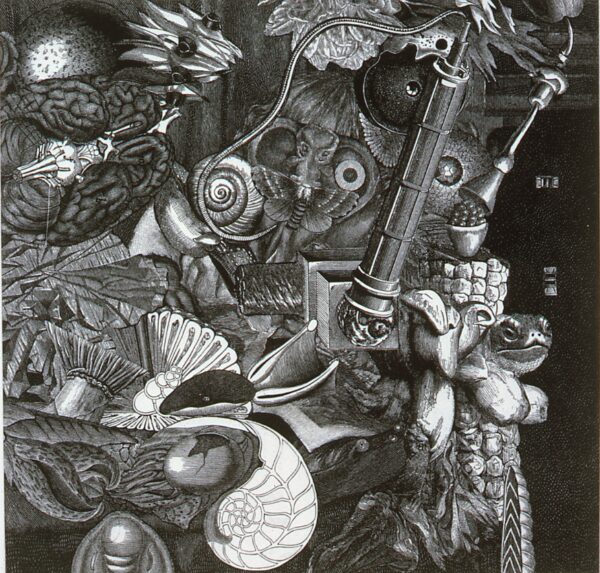

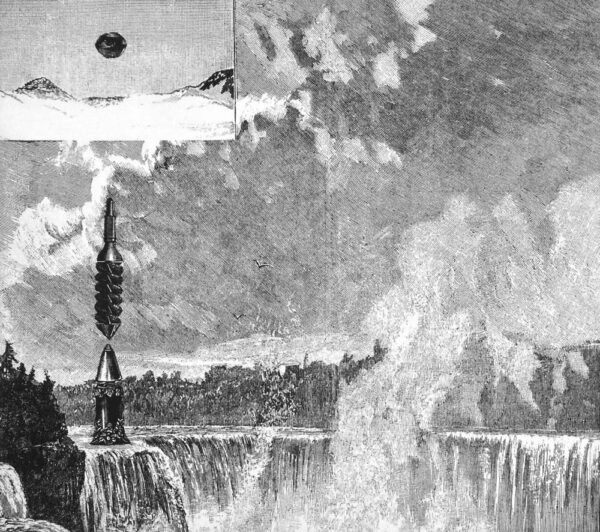

Photoetching.

8½ x 6½"; 18 x 15". 10.

Crown Point Press and Kathan Brown.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

Photoetching.

6½ x 5¼"; 18 x 15". 10.

Crown Point Press and Kathan Brown.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

Photoetching.

7 x 8"; 18 x 15". 10.

Crown Point Press and Kathan Brown.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

Photoetching.

5¾ x 10"; 18 x 15". 10.

Crown Point Press and Kathan Brown.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

Photoetching.

12¼ x 9"; 18 x 15". 10.

Crown Point Press and Kathan Brown.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

Photoetching.

8¼ x 6¼; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

11½ x 8¾"; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

14½ x 10¼"; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

9¼ x 9½"; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

9½ x 8¼"; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

7½ x 5½"; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

Photoetching.

5¾ x 21½"; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

9 x 11¼"; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

8¾ x 11½"; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

9 x 12½"; 19½ x 17". 10.

Crown Point Press and Patricia Branstead.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

Photogravure printed in color on gampi paper chine collé.

13 x 18¾"; 24 x 19". 10.

Crown Point Press and Gwen Gugall.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

10 x 16"; 24 x 19". 10.

Crown Point Press and Gwen Gugall.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

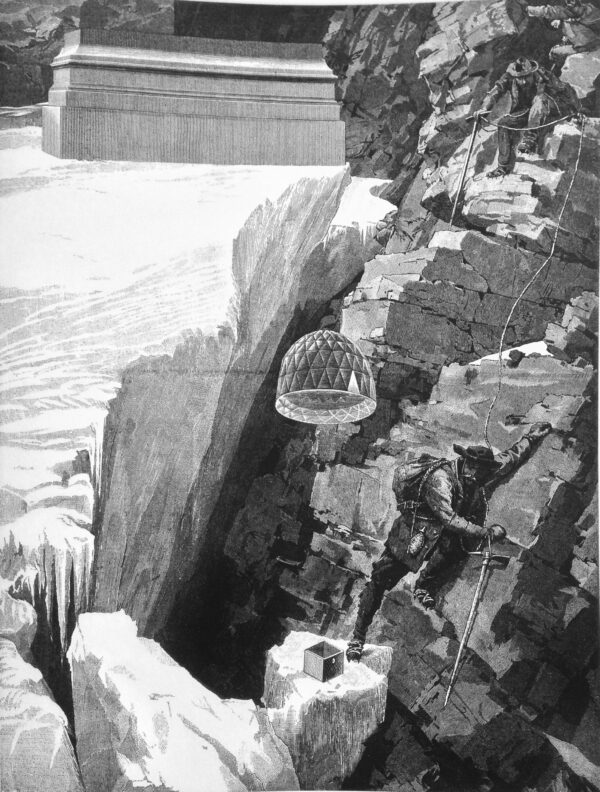

Photoetching.

9¼ x 9¾"; 24 x 19". 10.

Crown Point Press and Gwen Gugall.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

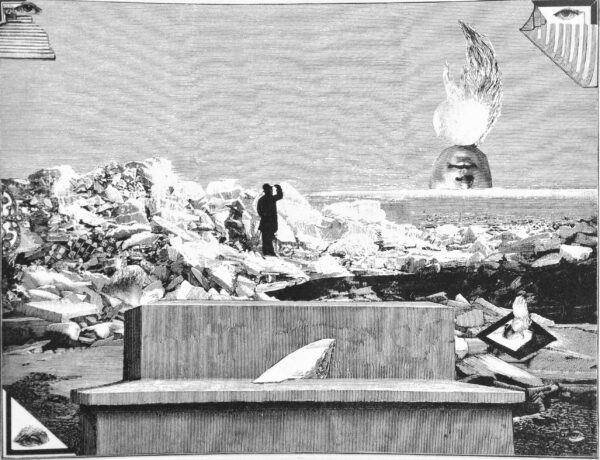

Photoetching.

8 x 9"; 24 x 19". 10.

Crown Point Press and Gwen Gugall.

$7,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

Photoetching.

9¼ x 12"; 24 x 19". 10.

Crown Point Press and Gwen Gugall.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

Photoetching.

19 x 12¾"; 24 x 19". 10.

Crown Point Press and Gwen Gugall.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

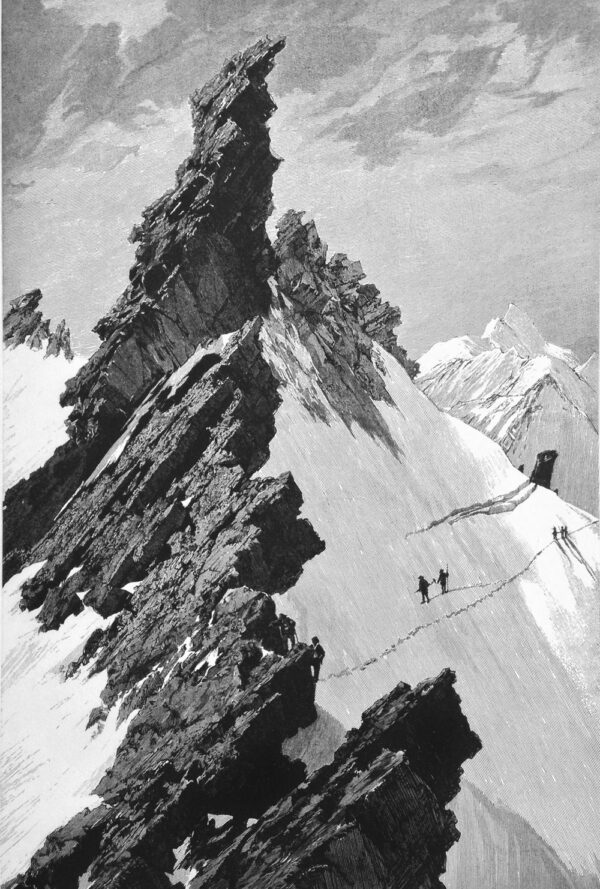

Photoetching.

18½ x 13¾"; 24 x 19". 10.

Crown Point Press and Gwen Gugall.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable

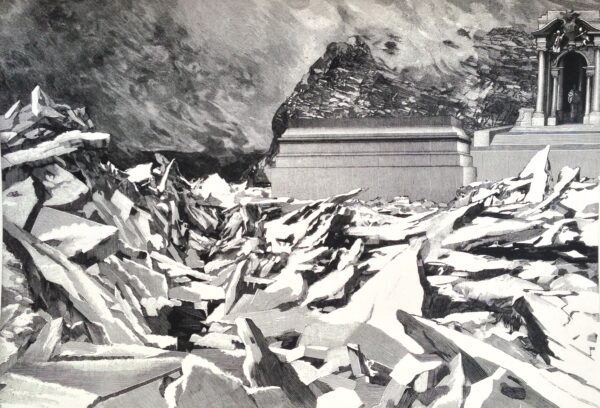

Photoetching.

12½ x 18½"; 24 x 19". 10.

Crown Point Press and Gwen Gugall.

$7,500 fair market value Unavailable