Christian Boltanski was born in Paris in 1944, the son of a Catholic mother and a Jewish father who was hidden in the family basement throughout the Nazi occupation. Young Christian was born on the day France was liberated. At the age of 12, Boltanski left school. He stayed at home making paintings and sculptures in his bedroom and learning English from his older brother, a linguist.

In a 1991 interview in Tate Magazine, Boltanksi said, “What drives me as an artist is that I think everyone is unique, yet everyone disappears so quickly.” Since 1967 he has made artworks using traces that people leave behind such as photographs and lost belongings. His works are memorials to everyone—to individuals as well as anonymous persons.

In 1971 Boltanski had a solo show at the Sonnabend Gallery in Paris, followed by a 1972 exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Since that time he has kept up a brisk worldwide exhibition schedule. In 1972 he was included in the Venice Biennale, then exhibited in subsequent Biennales in 1980, 1986, 1993, 1995, and 2003.

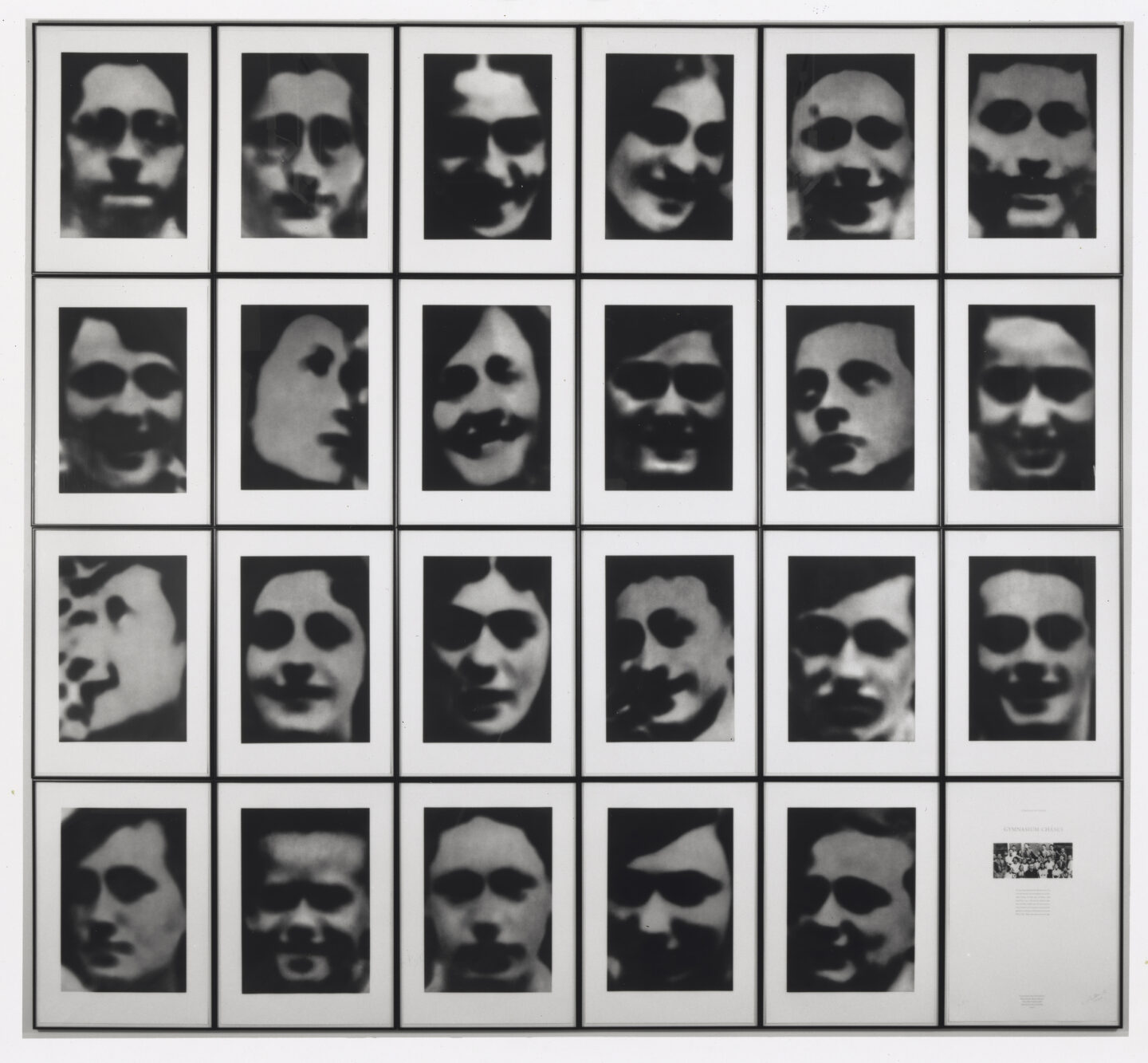

Boltanski’s work frequently deals with the Holocaust, although not explicitly. In Altar to Lycee Chases (1986-88), for example, indistinct photographs of the 1931 graduating class of a Jewish high school in Vienna are lit by inexpensive gooseneck lamps that obscure as much as illuminate the image and also invite associations with interrogation. The work serves as a memorial for the millions killed without naming anyone. In 1991 Boltanski expanded that project with a portfolio of photogravures titled Gymnsium Chases, published by Crown Point Press. Other works, such as The Reserve of Dead Swiss, 1990, made of photographs of Swiss citizens collected from newspaper obituaries, memorialize people who have died in ordinary ways.

In a 2002 interview in Tate Magazine Boltanski relates a story from Proust of a man who was on his way to kill himself but was distracted by something beautiful he saw along the way. According to Boltanski, forgetting saved the man. His memorials celebrate forgetting as a part of survival. In a 1989 interview with Liz Lufkin for the San Francisco Chronicle, Boltanski said, “the only thing I want is for people to be emotional, to laugh or cry. Most people don’t dare to say that, because it seems stupid, but that’s what I want.”

Christian Boltanski has had solo exhibitions at major institutions all over the world including the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany. Recent solo exhibitions include the Centre Pompidou in Paris, 2019; the National Art Center in Tokyo, 2019; The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, 2018; and the Museo del Arte Moderna di Bologna, Italy, 2017. Boltanski’s work is in many public collections in Europe and the United States including the Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Hirshhorn Museum, Washington DC, the Tate Collection, London, and the Pompidou Center, Paris. He is married to French artist Annette Messenger and lives in Malakoff, a suburb of Paris. He is represented by the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York and Paris.

—Kim L. Bennett, Crown Point Press