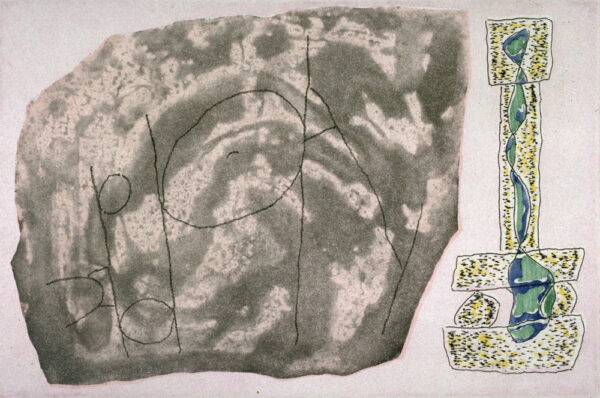

Hard ground etching with soap ground aquatint and aquatint.

6 x 4"; 14¾ x 12". 15.

Crown Point Press and Pamela Paulson.

$850 InquireInquire

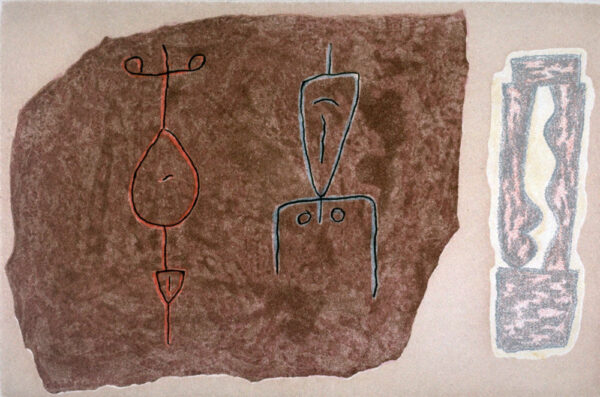

Color hard ground and soft ground etching with soap ground aquatint.

4 x 6"; 12 x 15". 15.

Crown Point Press and Pamela Paulson.

$1,500 fair market value Unavailable

Color soft ground etching with soap ground and spit bite aquatints.

4 x 6"; 12 x 15". 15.

Crown Point Press and Pamela Paulson.

$1,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

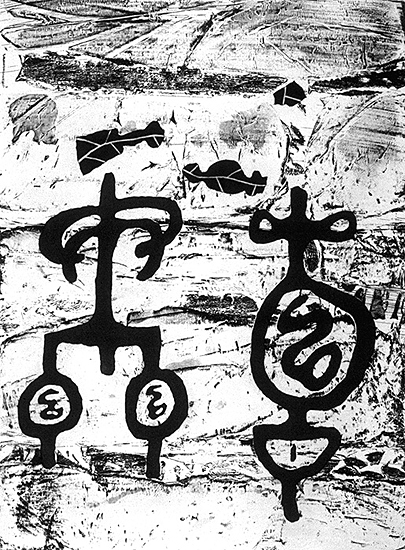

Soap ground aquatint with aquatint.

23¾ x 17¾"; 38 x 30". 15.

Crown Point Press and Pamela Paulson.

$2,000 InquireInquire

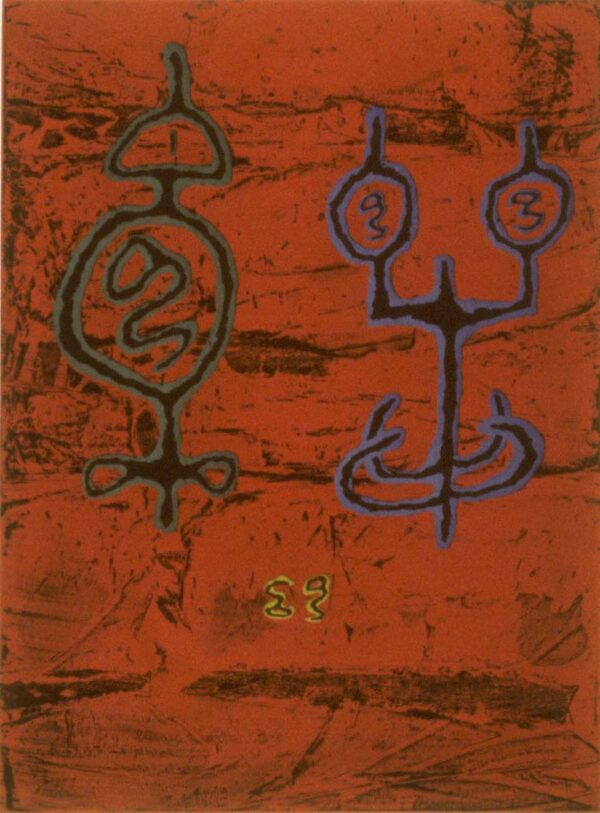

Color soap ground and spit bite aquatints.

23¾ x 17¾"; 38 x 30". 15.

Crown Point Press and Pamela Paulson.

$2,000 fair market value Unavailable

Soup ground and spit bite aquatints.

11½ x 10¾"; 20½ x 19". 15.

Crown Point Press and Pamela Paulson.

$1,800 InquireInquire

Color soap ground and spit bite aquatints.

11½ x 10¾"; 20½ x 19". 15.

Crown Point Press and Pamela Paulson.

$1,800 fair market value Unavailable

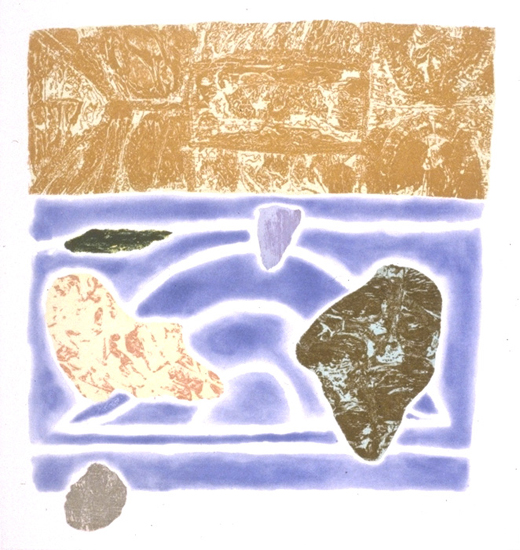

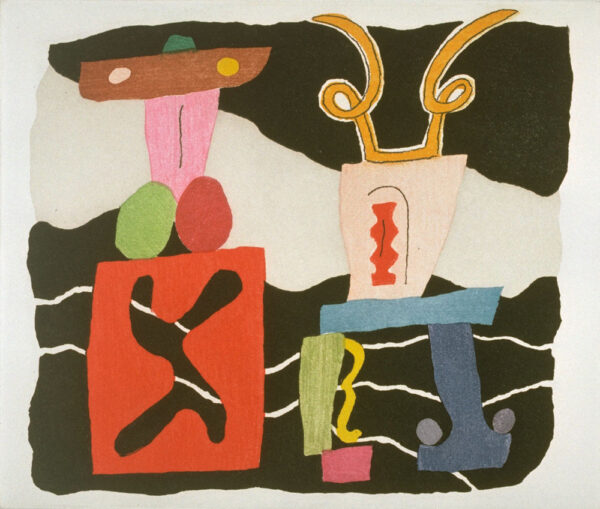

Color woodcut.

36 x 23¾"; 41 x 28". 100.

Crown Point Press and Tadashi Toda.

$3,500 InquireInquire

Color aquatint with soft ground and hard ground etching, spit bite aquatint and engraving.

4 x 6"; 12 x 15". 25.

Crown Point Press and Hidekatsu Takada.

$950 fair market value Unavailable

Color aquatint with soft ground and hard ground etching, spit bite aquatint and engraving.

4 x 6"; 12 x 15". 25.

Crown Point Press and Hidekatsu Takada.

$950 fair market value Unavailable

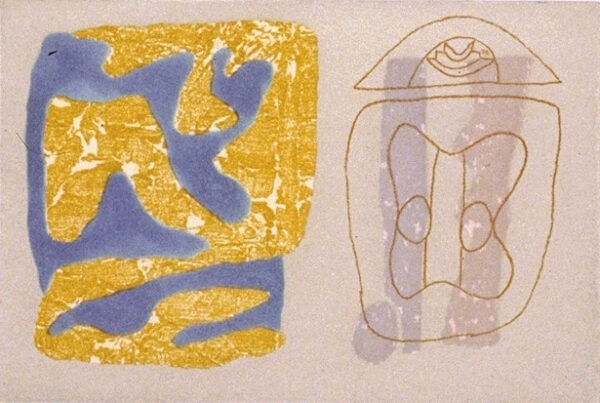

Color aquatint with soft ground and hard ground etching and spit bite aquatint.

4 x 6"; 12 x 15". 25.

Crown Point Press and Hidekatsu Takada.

$950 fair market value Unavailable

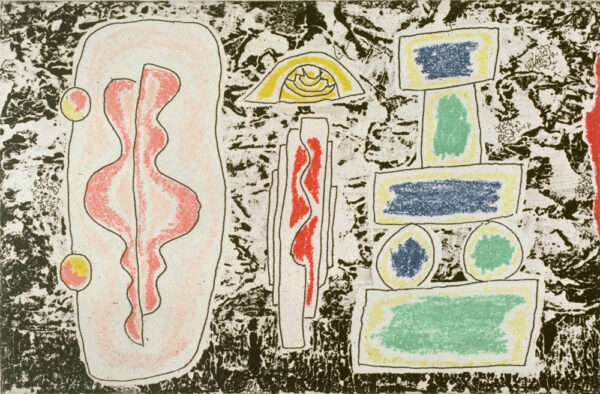

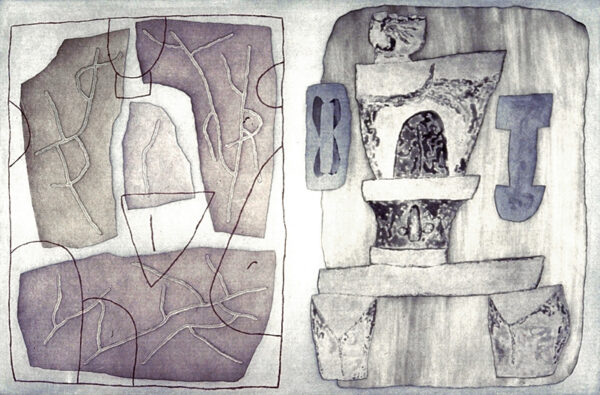

Color soft ground etching with aquatint.

6 x 8"; 16 x 16". 25.

Crown Point Press and Hidekatsu Takada.

$1,500 fair market value Proof AvailableProof Available

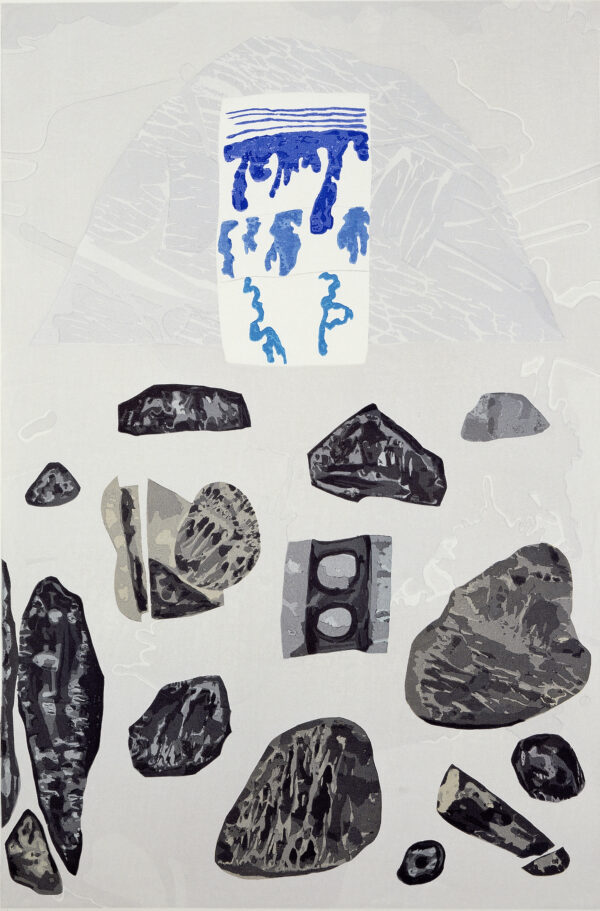

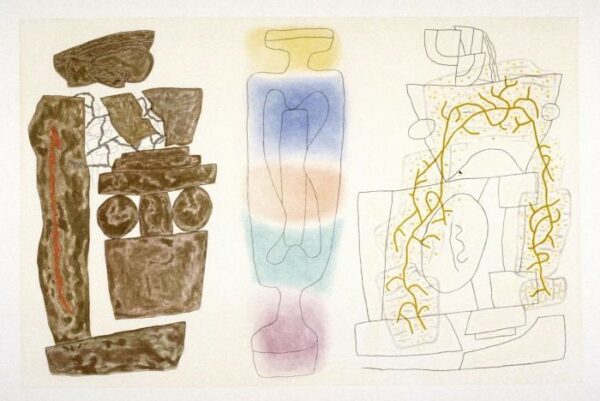

Color aquatint with hard and soft ground etching and spit bite aquatint.

24 x 36"; 29¾ x 44". 25.

Crown Point Press and Hidekatsu Takada.

$4,000 fair market value Unavailable

Color aquatint with soft ground etching and spit bite aquatint.

24 x 36"; 30¾ x 44". 25.

Crown Point Press and Hidekatsu Takada.

$4,000 InquireInquire